Home Improvements Contracts

August 22, 2012Consumer Protection

One of actor Tom Hanks’ more forgettable roles was as a beleaguered homeowner in The Money Pit. Hanks and his wife, played by Shelley Long, move into a “fixer upper” house with plans to renovate it. At one point, water is streaming out of the house in the background. A plumber hands Hanks a huge bill, declares that he is late for his daily golf game, jumps into his Corvette and disappears.

One of actor Tom Hanks’ more forgettable roles was as a beleaguered homeowner in The Money Pit. Hanks and his wife, played by Shelley Long, move into a “fixer upper” house with plans to renovate it. At one point, water is streaming out of the house in the background. A plumber hands Hanks a huge bill, declares that he is late for his daily golf game, jumps into his Corvette and disappears.

While the scene is funny, there may be an eerie familiarity to it if you own a home. And chances are, the scenario is also familiar to some of your clients who are homeowners. Few of them will ever be hurt seriously in an automobile accident or terminated wrongfully. But many will experience problems with the people to whom they have entrusted their most valuable asset – their home.

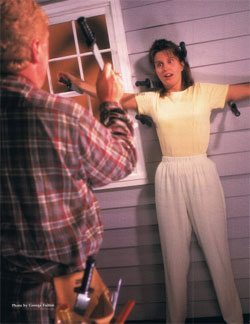

Here are some of the “tools” that can be used to prevent a home improvement job from turning into The Money Pit. Or, at least, to do a decent job of repairing the damage if it does.

AVOIDING THE “RUSTY NAILS” OF THE HOME IMPROVEMENT INDUSTRY

Without question, there are many scrupulous, honest and skilled home repair and improvement contractors. But this article is not about them. So instead we will focus on the exploits of contractors like “Rusty Nails Home Improvements.” Although the names are fictional, the story below is based on actual events that have occurred in South Carolina. Rusty Nails is in the business of selling and installing vinyl siding, windows and other home improvement products and services. One day, Rusty shows up on the doorstep of Ms. Colleen Consumer. Colleen’s house is obviously in need of work, and Rusty attempts to sell her vinyl siding and replacement windows. He has a “one day only” special that seems like a good deal. Colleen is a single mother of two children. By almost anyone’s standards, she is low-income. The modest home is her first and she purchased it only the year before with HUD financing. In addition to the first mortgage on the home and the responsibility of her children, Colleen has many other debts. Although she wants badly to improve the appearance of her home, she tells Rusty that she cannot afford the $5,000 price he has quoted. But Rusty has a “solution” to this problem. He offers to secure financing not only for the $5,000, the cost of the improvements, but for an additional “debt consolidation” loan of $10,000. Neither the interest rate nor term of the loan is discussed, and Rusty neglects also to inform Colleen that the loan will be secured by a mortgage on her home.

The next day, Rusty shows up at Colleen’s house with a retail installment contract. The contract is printed on a form from The Cash Factory, a lender. The contract recites that $15,000 is the price of the improvements.

This sum is to be financed at 16 percent for 20 years. The total cost to Colleen over the life of the loan will be in excess of $50,000. The contract does not mention any sum being remitted to Colleen for “debt consolidation” as promised. Colleen signs the contract.

A few days later, Rusty brings over some more “paperwork” for Colleen to sign “so that the work can begin.” Among these documents are a mortgage and a certificate indicating that the work has been completed.

Anxious for the beautification of her home, Colleen again signs. Shortly after the contract is executed, Rusty forwards it to The Cash Factory. The Cash Factory funds the project and forwards Rusty a check for $15,000. The Cash Factory immediately sells and assigns the note and mortgage to Currency Corporation.

Three months pass. No work on the house has begun. At first, Rusty answers Colleen’s telephone calls with excuses about building material delays and promises that work will begin shortly. At one point, he pacifies her by promising to install an air conditioner free of charge. But now Colleen’s calls simply go unanswered.

However, the telephone calls and letters to Colleen from Currency Corporation discussing “foreclosure” have just begun.

How could Colleen have avoided dealing with Rusty in the first place? According to the Federal Trade Commission, which fields thousands of consumer complaints about home improvement contractors each year, the best place to get the name of a good contractor is from a friend, neighbor or co-worker who has used the contractor. Local trade organizations can provide the names of area members in good standing.

Consumers can also contact their local Better Business Bureau and the South Carolina Department of Consumer Affairs to determine if complaints have been lodged against the contractor in the past. For example, if Colleen had called the Department of Consumer Affairs and inquired of Rusty, she would have learned that other consumers had lodged more than 20 complaints against him.

Colleen would also have been smart to ask for a copy of Rusty’s current insurance certificates and licenses. Before agreeing to anything, she should have obtained a written estimate for the work and compared it against estimates from other contractors on identical project specifications.

Once agreed upon, the work to be performed, the price and any guarantees, warranties or promises made should have been put in writing. The contract should also recite the start and completion dates of the work. When a door-to-door solicitation sale is involved, even more caution is needed. Homeowners like Colleen should never agree to a deal that is “now or never” and should be highly suspicious of contractors who claim to be “in the neighborhood” with “leftover” materials from a nearby job. One such scheme in Southern California left homeowners soaked after hard rains revealed that “leftover” roofing tar was, in fact, used motor oil.

IT MAY NOT BE “OPPORTUNITY” KNOCKING ON THE DOOR

Like Colleen’s transaction with Rusty Nails, many home repair and improvement contracts begin with door-to-door, face-to-face contact between the contractor and consumer.

The significance of this is that home solicitation sales are regulated by the South Carolina Consumer Protection Code. South Carolina Code § 37-2-501 defines a “home solicitation sale” as a consumer credit sale that is negotiated face to face at the residence of the consumer.

Excluded from home solicitation sales are sales made pursuant to a preexisting revolving charge account and transactions conducted entirely by mail or by telephone. The fact that a credit sale is made at a consumer’s home gives the consumer special rights. Chief among these is that the consumer has the right to cancel the transaction, without cost, by midnight of the third business day following its execution. For example, if Colleen signed the contract with Rusty on a Tuesday, she would have until midnight on Friday to cancel. S.C. Code § 37-2-502(1). Cancellation could have been made by sending a written notice to Rusty and would have been complete upon mailing. S.C. Code § 37-2-502(3).

It is important to remember that this three-day “cooling off” period begins to run only after the seller has given the consumer a written statement of her right to cancel the transaction. This statement must be given to the consumer (and signed by the consumer) in every case, unless the consumer requests that the seller is to provide the goods or services “without delay in an emergency.” §§ 37-2-502(5); 37-2-503(1). If the seller fails to give this notice, the consumer can cancel at any time, “by notifying the seller in any manner.” § 37-2-503(3).

There is thus a potential escape hatch in every home improvement contract that involves a door-to door sale. But what happens after the contract is canceled? First, within 10 days of cancellation, the seller must return the consumer’s down payment, any goods traded in and any evidence of indebtedness. Until the seller does so, the consumer retains possession of any goods delivered to him by the seller and has a lien on the goods in his possession or control for any recovery to which he is entitled. § 37-2-504.

Second, the consumer must return to the seller any goods received under the sale within 40 days. The consumer is required to make this tender only at her residence. If the seller fails to demand possession of the goods within “a reasonable time” after cancellation (which is presumed to be 40 days), the consumer, without obligation to pay, can retain the property. § 37-2-505(1).

Moreover, under the Truth in Lending Act, if the goods have been affixed to the consumer’s property, the consumer may be able to argue that any tender obligation constitutes “actual damages” arising from the seller’s failure to notify the consumer of his rescission rights. § 6.8.4.3, National Consumer Law Center, Truth in Lending (3rd ed. 1995).

At most, the tender should be the “reasonable value” of the work performed, which may be far less than the payoff amount. Official Staff Commentary, Truth in Lending Act, Reg. Z §§ 226.15(d)(3)-2, 226.23(d)(3)-2.

One way that dishonest contractors have attempted to get around the consumer’s right to rescind is a practice called “spiking.”

“Spiking” happens when a contractor begins work within the cancellation period and then tells the consumer a) that the contract cannot be canceled because work has begun or b) that he is entitled to be paid for the value of the work thus far completed. §6.8.4.2, National Consumer Law Center, Truth in Lending (3rd ed. 1995). A first cousin to spiking is the so-called “two-contract dodge.”

As its name implies, under this scenario, two contracts are used to avoid rescission by the consumer. First, the contractor first executes a sales contract with the consumer for the improvements. Full payment is due on completion. All the while, however, the contractor represents to the consumer that he can arrange financing for the job. A second contract is thus set up as a “loan” from a third-party lender to pay off the first “sales” contract. § 6.8.4.2.2. National Consumer Law Center, Truth in Lending (3rd ed. 1995).

How does this deprive the consumer of her rights? Although both contracts may contain a notice of the consumer’s right to cancel, the consumer is never told the actual cost of the work, including financing, until after the work is done. At that time, the cash price of the job has come due. Naturally, the consumer feels that she must accept the financing. Most likely, she also believes that she cannot now cancel the job because the work is complete.

Courts considering the question have generally held that the “two contract dodge” violates the Federal Truth in Lending Act’s three day delay in performance rule. See, e.g., Jetton v. Caughron, Clearinghouse No. 43, 745A, No. 3-87-0126 (M.D. Tenn. 1988); 28 Doggett v. County Savings & Loan Association, 373 F. Supp. 774 (E.D. Tenn. 1973). § 6.6.8.4.2.2, National Consumer Law Center, Truth in Lending (3rd ed. 1995).

The rationale of the courts is that the consumer has been deprived of his right to compare between the prices offered by competing contractors and is unaware of the true cost until after the work is done. The same result would arguably obtain under the South Carolina Consumer Protection Code, which incorporates the Truth in Lending Act (TILA) at § 37-5-203.

FINANCING FOR HOME IMPROVEMENTS IS NOT ALWAYS ON THE LEVEL

Colleen’s case is typical also in that the price of the improvements is to be financed. This makes it a “credit sale” under the South Carolina Consumer Protection Code. S.C. Code § 37-2-104 defines a “credit sale” as any sale of goods, services or an interest in land in which: credit is granted by a person who regularly engages as a seller in credit transactions of the same kind; the buyer is a person other than an organization; the purchase is for personal, family, or household use; the debt is to be paid in installments or a credit service charge is to be made; and the cash price of the transaction is for less than $65,000 (this amount is periodically reviewed and may increase after June 30, 2000). When a transaction is characterized as a “credit sale,” it becomes subject to a battery of limitations.

For example, the creditor cannot charge interest in excess of 18 percent without filing a notice of intent to do so each fiscal year with the Department of Consumer Affairs and posting the highest rate intended to be charged conspicuously where business is transacted. Beyond the finance charge, the creditor is limited to receiving only the “additional charges” allowed by S.C. Code § 37-2-202.

And if the creditor requires a cosigner, the creditor must give the co-signer a separate written notice of his or her liability—otherwise, the co-signer cannot be made liable for the debt. S.C. Code § 37-2-303. Additionally, on any installment payment the consumer has a 10-day statutory grace period before a late fee may be assessed. S.C. Code § 37-2-203.

Most consumer credit transactions are also covered by the federal TILA, which is Congress’s attempt to ensure that the cost of credit is accurately disclosed to consumers so that they can make informed choices. Rodash v. AIB Mortgage Co., 16 F.3d 1142 (11th Cir. 1994). Although a discussion of the TILA is beyond the scope of this article, lawyers should be aware that Regulation Z requires the creditor to make a “meaningful” written disclosure of credit terms, including the interest rate (expressed as an annual percentage rate) and the finance charge, so that consumers will understand the true cost of credit and be able to comparison shop.

Like South Carolina’s home solicitation statute, the TILA gives homeowners the right to rescind most home improvement credit sales for which the home is taken as collateral. 15 U.S.C. § 1635(a). But, under the TILA, the right may be preserved for as long as three years if TILA disclosures were not made originally and the home has not been sold. Beach v. Ocwen Federal Bank, 1998 WL 183852 (U.S. S.Ct. April 21, 1998).

The consumer also has a private cause of action under the TILA for actual damages, statutory damages of twice the finance charge (not to exceed $2,000) and attorney’s fees if proper disclosures are not made. In certain “highcost” mortgage loans, the creditor must meet additional disclosure requirements. Material disclosure violations in high cost mortgage loans can cause the consumer’s damages to be as high as “the sum of all finance charges and fees paid by the consumer.” Home Ownership and Equity Protection Act of 1994, §153(a), amending 15 U.S.C. § 1640(a). Similar recovery is available under the South Carolina Consumer

Protection Code. S.C. Code § 37-5-203. The consumer must elect which claim (federal or state) he or she intends to pursue. S.C. Code § 37-5-203(7). The statute of limitations to bring a claim under state law is two years, as opposed to one year for the TILA. Notwithstanding these time limits, a TILA violation can be raised defensively at any time to reduce or “recoup” the claims of a creditor. Tuloka Affiliates, Inc., v. Moore, 275 S.C. 199, 268 S.E.2d 293 (1980).

MORTAR AND MORTGAGES DON’T ALWAYS MIX

The fact that home improvement financing is often secured by a home mortgage has significance even beyond the TILA implications discussed above. In South Carolina, home mortgage brokering is regulated by the South Carolina Residential Mortgage Loan Broker Act. The Act broadly defines a mortgage loan broker as “a person or organization who brings borrowers or lenders together to obtain mortgage loans.” S.C. Code § 40-58-20(3).

No person may bring together borrowers and lenders for his or her “direct or indirect gain” unless he or she is licensed as a mortgage broker by the South Carolina Department of Consumer Affairs.

A violation of the General Loan Brokers Act, i.e., unlicensed brokering, may result in civil and criminal penalties. A violation of the General Loan Brokers Act is also a per se violation of the South Carolina Unfair Trade Practices Act. (UTPA). Mortgage Loan Brokers, by Jane Shuler, Esquire, p. 9; S.C. Code § 39-5-20.

The UTPA is potentially one of the heftiest hammers in the consumer’s toolbox. “Willful and knowing” violations of the UTPA can lead to awards of three times actual damages, plus attorney’s fees and costs. In the example above, Rusty Nails has brought Colleen Consumer and The Cash Factory together for his gain. Rusty is not even a licensed contractor, much less a licensed mortgage broker, and may be liable to Colleen under the UTPA, among other things.

Another critical omission in the Rusty Nails/Colleen Consumer transaction is the failure to obtain Colleen’s preference on an attorney to close the mortgage loan. A closing attorney would not only have answered Colleen’s questions but would likely have raised the questions that Colleen should be asking.

South Carolina Code § 37-10-102 recognizes the importance of counsel in protecting the consumer’s interests in a mortgage loan transaction. When the consumer is deprived intentionally of her opportunity to choose a closing attorney, she may be entitled to recover a penalty of as much as $7,500, plus attorney’s fees. §37-10-105. Even greater damages (up to twice the total amount of the loan finance charge) may be recovered if a court determines that the underlying transaction was unconscionable. § 37-5-105(C)(4). The court can also refuse to enforce the agreement. § 37-5-105(C)(1).

THE “DEEP POCKET” UNDER THE INSOLVENT CONTRACTOR’S TOOLBELT

A lawyer from Columbia once boasted that he had put four kids through college suing “judgment proof” defendants. That sounds like a hard way to make a living.

Fortunately, the South Carolina Consumer Protection Code imposes liability on assignees of the contractor and lenders involved in the transaction. South Carolina Code § 37-2-404 subjects an assignee of the contractor/seller’s rights to “all claims and defenses” of the consumer against the seller, even though the assignee is a holder in due course or the consumer has purported to waive his claims and defenses as against the assignee. Rosemond v. Campbell, 288 S.C. 516 (Ct.App. 1986). And South Carolina Code § 37-3-410 provides that lenders are subject to all claims and defenses in many situations, particularly where the lender has past dealings with (and knows of complaints about) the contractor. The liability of the lender or assignee is not unlimited, however.

Generally, the statute restricts recovery to the amount due on the obligation at the time the assignee or lender has written notice of the claim. §§ 37-2-404(2); 37-3-410(2). Any damages in excess of those recoverable against the assignee or lender can, of course, be recovered from the seller, since he is liable on the underlying contract of sale. Rosemond, supra.

These statutory limits may not apply, however, where the consumer can show that the contractor was acting as an “agent” of the lender or that a conspiracy existed between the two. In Baker v. Harper, an Alabama jury found in favor of five individual homeowners against a contractor and a lender, Union Mortgage. The jury awarded the homeowners a staggering $45 million dollars in actual and punitive damages. Although the verdict was later remitted to a “mere” $28 million, it demonstrates the volume of the “message” that jurors (experienced consumers themselves) are willing to send to lenders who engage in shady practices. § 5, National Consumer Law Center, Consumer Law Pleadings Number One (1994).

THE DEBT COLLECTION CONNECTION

The last tool is South Carolina Code § 37-5-108(4). This section prohibits persons from engaging in abusive or unconscionable practices in connection with the collection of a debt. Unlike the federal Fair Debt Collection Practices Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1692, § 37-5-108 applies to creditors collecting debts on behalf of themselves, in addition to thirdparty debt collectors.

Specific acts that are considered unconscionable under § 37-5-108 include threats of criminal prosecution against the consumer, the use of profanity and contacting the consumer at frequent intervals with a primary purpose of harassment. A debt collector also cannot “threaten to enforce a right with knowledge or reason to know that the right does not exist” or otherwise make “deceptive representations.” Unscrupulous collectors have been known to routinely threaten wage-garnishment, which as of this writing, is a right that does not exist in South Carolina. In the home-improvement context, misrepresentations are sometimes made about liens on the home, cancellation rights and foreclosures, all of which may be actionable.

Threatening statements such as a collector’s handwritten note warning “My special agents will remain in your area to collect. Believe me.” (not surprisingly) constituted an abusive, harassing and threatening statement under the FDCPA, as did a collector’s threat to have the consumer “picked up.” See, respectively, Grassley v. Debt Collectors, Inc., Clearinghouse No. 49, 145A (D. Or. 1992), Kizer v. American Credit & Collection, Clearinghouse No. 45, 928 (D. Conn. 1991). Both actions would likely violate § 37-5-108 as well.

If a consumer can prove a violation of § 37-5-108, he or she may recover a statutory penalty of up to $1,000, attorney’s fees and costs, and actual damages. Actual damages are often underestimated. Truly abusive, frequent contacts can cause extreme stress to the consumer targeted, for which damages may be recoverable.

Finally, as § 37-5-108 is not an exclusive remedy, it can be combined with other applicable common-law tort actions such as “outrage.”

SUMMARY

If a client is unsuccessful in avoiding an unscrupulous contractor, many options remain.

Investigate whether the contract can be canceled. If financing was involved, check to see whether the terms were disclosed accurately. Where financing is secured by a mortgage, find out who put the lender together with the client and whether the client’s lawyer preference was asked. Remember: even where the contractor appears “judgment proof” there may yet be a solvent entity who is responsible. Who knows? Maybe The Money Pit will turn out to be a gold mine.